Rise and fall of a prairie giant

André Magnan is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Social Studies at the University of Regina. His research examines the political economy of local and global food systems, with a focus on the history and politics of grain marketing on the Canadian prairies.

André Magnan is an associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Social Studies at the University of Regina. His research examines the political economy of local and global food systems, with a focus on the history and politics of grain marketing on the Canadian prairies.

Created in 1935, the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) was one of the most important institutions of the prairie grain economy. From 1943 until 2012, the CWB served as a “single-desk” seller of prairie grain. Under this system, the wheat board had the exclusive authority to sell wheat and barley on behalf of prairie farmers, returning to them all of the proceeds minus the costs of administration. The Canadian government stripped the wheat board of its “single-desk” on August 1st, 2012, ushering in the biggest change in prairie farming in at least two generations. The CWB’s long history is a testament to the cooperation – and conflicts – that shaped the prairie wheat economy over many decades.

Prairie farmers first seized on the idea of collective grain marketing in the early 1900s, when they had little economic clout. The early grain trade was organized and financed by large private interests such as banks, railways, grain elevators and Winnipeg grain merchants, the middlemen through which prairie grain was sold into world markets. Farmers complained of abuse at the hands of each of these players. Elevator agents, for instance, were accused of manipulating the grain scales and wheat grades, cheating farmers out of the full value of their deliveries. When it came to selling grain, farmers were at the mercy of grain merchants. In the fall, when there was a glut of grain on the market, grain buyers offered low prices in order to take advantage of farmers’ need to sell. Early farmers’ organizations pressed for “orderly marketing” as an antidote to this problem. By selling their grain collectively through a single agent they would have both greater marketing discipline – allowing grain to be sold over a long period of time, helping to even out price fluctuations -- and more negotiating power.

Prairie farmers first seized on the idea of collective grain marketing in the early 1900s, when they had little economic clout. The early grain trade was organized and financed by large private interests such as banks, railways, grain elevators and Winnipeg grain merchants, the middlemen through which prairie grain was sold into world markets. Farmers complained of abuse at the hands of each of these players. Elevator agents, for instance, were accused of manipulating the grain scales and wheat grades, cheating farmers out of the full value of their deliveries. When it came to selling grain, farmers were at the mercy of grain merchants. In the fall, when there was a glut of grain on the market, grain buyers offered low prices in order to take advantage of farmers’ need to sell. Early farmers’ organizations pressed for “orderly marketing” as an antidote to this problem. By selling their grain collectively through a single agent they would have both greater marketing discipline – allowing grain to be sold over a long period of time, helping to even out price fluctuations -- and more negotiating power.

It wasn’t until immediately after WWI, however, that the idea was first put into practice. During the war, the government had taken direct control of many aspects of the grain trade in order to meet its war-time obligations to Great Britain. In the aftermath of the war, the private grain trade failed, and the government stepped in to create the first wheat board for the 1919-1920 crop year. The board collected all prairie grain deliveries and sold the crop on behalf of farmers. Farmers received an initial payment on delivery and subsequent payments based on the progress of the sales campaign. They responded enthusiastically to the first wheat board, especially the benefits of receiving the same price for their grain, no matter when they delivered it. The government, however, considered the wheat board a temporary arrangement and dismantled it after one year. Farmers agitated for its reinstatement, igniting a years’ long struggle.

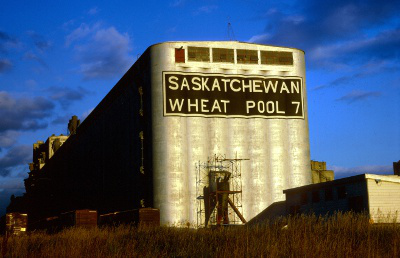

In the early 1920s, when it became clear the government would not restore the wheat board, farmers settled for the next best thing, which was to create voluntary, cooperative grain marketing agencies. Farmers’ movements and local organizers launched huge recruitment campaigns to sign farmers up for provincial “Wheat Pools”. After a false start in 1923, the big breakthrough came in 1924, when organizers managed to sign up 45 725 farmers for the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool.  Soon, the Pools were selling on average half of the annual prairie wheat crop, coordinating their sales through a Common Selling Agency. This worked reasonably well for a few years, but the farmer-owned Pools collapsed shortly after the onset of the Great Depression. Again, the government stepped in to save the wheat economy from the collapse of the private trade, first by taking over the Pools’ massive unsold grain stocks, then by reviving the wheat board in 1935.

Soon, the Pools were selling on average half of the annual prairie wheat crop, coordinating their sales through a Common Selling Agency. This worked reasonably well for a few years, but the farmer-owned Pools collapsed shortly after the onset of the Great Depression. Again, the government stepped in to save the wheat economy from the collapse of the private trade, first by taking over the Pools’ massive unsold grain stocks, then by reviving the wheat board in 1935.

From 1935 to 1943, the reincarnated Canadian Wheat Board accepted farmer deliveries on a voluntary basis, providing farmers with a guaranteed minimum price. This proved problematic because farmers tended only to deliver to the board when the open market price was lower than the guaranteed price, triggering large deficits covered by the federal government. During World War II, the mixed system also interfered with the government’s ability to coordinate grain sales to its allies. The government finally re-established the single-desk in 1943. This policy had the support of all political parties, and was cheered by prairie farmers.

For the next seven decades, the single-desk system served as a means of mitigating marketing risks and improving farmer bargaining power in world markets. The wheat board evolved with changing commercial and political circumstances, but retained its core mandate – to maximize returns for prairie farmers. By the 1980s, however, some segments of the farming community began to oppose the CWB’s marketing monopoly, arguing that it was too restrictive for business-oriented farmers. Specialized commodity organizations such as the Western Canadian Wheat Growers’ Association and the Western Barley Growers Association, in particular, began to push for the board’s deregulation. In the mid-1990s, some anti-CWB farmers delivered wheat directly to U.S. grain elevators, breaking the Canadian Customs’ Act, an action for which some of the farmers were subsequently fined and, refusing to pay their fines, jailed. For the farmers, this was a symbolic protest against the restrictions the CWB system imposed on their ability to sell their grain to any buyer, domestic or foreign, without restriction.

As the issue became increasingly controversial, governments struggled to respond. In 1993, the Progressive Conservative government tried to unilaterally remove the board’s marketing monopoly on barley, but was blocked by a successful court challenge on behalf of farmers’ organizations. The Chrétien Liberal government, elected in 1993, appointed a Western Canadian Grain Marketing Panel to provide recommendations on the future of the CWB. When the panel suggested partial deregulation, the Minister in charge of the wheat board, Ralph Goodale, insisted that farmers first be consulted. The government conducted a plebiscite on the barley question in 1997, and 62 per cent of farmers voted in favour of retaining the single-desk system. Committed to giving farmers more control over the agency, the government reformed the CWB’s governance in 1998. Henceforth, all changes to the board’s mandate would be subject to a farmer plebiscite and the approval of a farmer-controlled board of directors. These changes allowed the CWB to bring in some new initiatives, including more flexible pricing and delivery options, and generally improved the board’s legitimacy in the eyes of farmers.

In 2006, the newly elected Conservative government reignited the CWB controversy. The Conservatives have adamantly opposed collective grain marketing through the CWB, especially since the merger of the Reform Party and the Progressive Conservatives in 2003. They have sought a “dual market” in which farmers could choose to sell to any buyer, including a deregulated version of the CWB. The viability of the “dual market” was questioned by CWB supporters, however, since there was little reason to believe that a deregulated wheat board could deliver the same benefits to farmers, or indeed survive. Unlike the large multi-national grain companies that dominate the market, the CWB doesn’t own its own network of grain elevators.  In 2007, the Conservatives moved to implement a “dual market” for barley, based on the results of its own plebiscite. In the 2007 plebiscite, 38 per cent of farmers voted for the single-desk, 48 per cent for marketing choice (i.e., the “dual market”), and 14 per cent for an open market. Combining the tallies for the second and third choices, the government concluded that the majority of farmers wished to remove the single-desk. Ultimately, however, the government was prevented from enacting the change because of its inability, as a minority government, to muster enough parliamentary votes to change the CWB Act.

In 2007, the Conservatives moved to implement a “dual market” for barley, based on the results of its own plebiscite. In the 2007 plebiscite, 38 per cent of farmers voted for the single-desk, 48 per cent for marketing choice (i.e., the “dual market”), and 14 per cent for an open market. Combining the tallies for the second and third choices, the government concluded that the majority of farmers wished to remove the single-desk. Ultimately, however, the government was prevented from enacting the change because of its inability, as a minority government, to muster enough parliamentary votes to change the CWB Act.

With its majority electoral win in 2011, the Conservative government once again set about to strip the CWB of its single-desk. When the wheat board conducted its own plebiscite, in August 2011, finding that 62 per cent of farmers wished to retain the single-desk for wheat and 51 per cent the single-desk for barley, the government disregarded the results. The government moved swiftly to introduce legislation that disbanded the farmer-controlled board of directors and, as of August 1st, 2012, stripped the board of its single-desk powers. The CWB (since rebranded Canadian Wheat and Barley) became a government-backed grain company, competing with private players for farmers’ grain deliveries. The new CWB was given a maximum of five years during which to present a plan for privatization, after which point the government would withdraw its financial backing and oversight of the company.

In the push to dismantle the CWB, the Conservative government argued that their policy of “marketing freedom” will provide the best of both worlds. Farmers are now free to sell to any buyer, including a deregulated CWB. Yet, in the new environment, the CWB is just another grain company – a very small one at that – and has lost the farmer-centred mandate that was its hallmark. And yet, not much has changed in farmers’ position in grain markets. The world grain trade is more concentrated than ever, and wheat buyers tend to be large food processing conglomerates. Grain companies such as Cargill, Richardson, and Glencore (the Swiss company that absorbed prairie-based Viterra in 2012) stand to benefit from the end of the single-desk by absorbing some (or all) of the CWB’s former business. Food processors will likely pay less for Canadian grain, as multiple sellers bid against one another to make the sale. For their part, farmers have lost an important tool of economic cooperation. By some estimates, the negotiating power of the single-desk was worth $CAD 400 – 500 million per year to prairie farmers.

Bibliography

Fairbairn, Garry. 1984. From prairie Roots : The Remarkable Story of Saskatchewan Wheat Pool. Saskatoon : Western Producer Prairie Books.

Morriss, W. E. 1987 and 2000. Chosen Instrument: A History of the Canadian Wheat Board, Volumes 1 and 2. Winnipeg: Canadian Wheat Board.

Pugh, T. and D. McLaughlin, editors. 2007. Our Board, Our Business: Why Farmers Support the Canadian Wheat Board. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

Wilson, C.F. 1978. A Century of Canadian Grain. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books.