Myron Momryk is a historian with the National Archives of Canada. He is a specialist in the history of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion and Canadian immigration history.

Myron Momryk is a historian with the National Archives of Canada. He is a specialist in the history of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion and Canadian immigration history.

After several years of political instability in Spain, the Spanish Civil War erupted on 18 July, 1936 when Spanish Army officers attempted to overthrow the Republican Government. The rebellion was led by a junta of officers who had the support of various monarchist, nationalist, right-wing and fascist political parties and movements. The Republican Government was left without any significant military forces for its own defence. Almost immediately the junta, led by General Francisco Franco and other military leaders, was able to obtain military and material support, most notably from Germany and Italy, which eventually included large contingents of trained soldiers and technicians. The various Spanish labour unions, left-wing political parties and anarchist movements formed their own militias and military units to defend the Republican Government. Among the first volunteers were a number of foreigners including individual Canadians who were living or travelling in Europe. Most of the early volunteers fought with little or no military training.

As the opposing sides sought the political, diplomatic and especially military support from foreign governments in their struggle, the Spanish Civil War escalated into a prolonged international crisis. Representatives of the Communist Party of Canada (CPC) were among the first foreign observers in Spain to assess the political and military situation. An international Non-Intervention Committee was formed in September, 1936 in London, England to support nonintervention by foreign governments and to prevent the Civil War from escalating into a general European war.

As the number of foreign volunteers grew in support of the Republican Government, the International Brigades were established and reorganized according to language groups to incorporate existing and new volunteers. The International Brigades were intended to act as instructors and examples to the Spanish recruits while a new Spanish Army was formed and trained to defend the Republican Government. The recruitment campaign in Canada was organized and administered by the Communist Party of Canada. Individuals with military training were encouraged to volunteer. The large majority of the volunteers were CPC members and the CPC screened the volunteers to ensure that only their supporters and sympathizers would receive assistance to travel to Spain. A few individual Canadian volunteers made their own way to Spain.

In Canada, volunteers travelled to Montreal or Toronto where they were interviewed, received physical examinations and acquired the proper documentation to travel to Spain. They usually journeyed in groups by bus or train to New York where they boarded ships for Europe. Others boarded ships in Montreal. Once across the Atlantic Ocean, they landed in France and were guided to Paris where they were sheltered in designated hotels and residences. From Paris they travelled south to the Spanish border and led by local guides, crossed on foot and in secret across the Pyrenees Mountains.

Once in Spain, the volunteers were met by representatives of the International Brigades. They received limited military training and were soon assigned to their units. Most Canadians served in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion and by February, 1937 there were approximately forty Canadians in this unit. The first Canadian casualties fell in February in military actions by the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. The weapons and other military equipment of the International Brigades were often obsolete and of mixed quality due to the difficulty in obtaining international support by the Republican Government. Among the few foreign states that provided military assistance was the Soviet Union.

In Canada, the federal government adopted a policy of non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War following the example of Great Britain, France and other European states.  The federal government became concerned with the large number of volunteers leaving for Spain and in April 1937 passed a new Foreign Enlistment Act outlawing participation by Canadians in foreign wars. On July 31, 1937 the Act was applied to the enlistment by Canadians on any side in Spain. The recruitment campaign which was discreet went underground. However, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police continued to investigate the recruitment activities of the Communist Party of Canada.

The federal government became concerned with the large number of volunteers leaving for Spain and in April 1937 passed a new Foreign Enlistment Act outlawing participation by Canadians in foreign wars. On July 31, 1937 the Act was applied to the enlistment by Canadians on any side in Spain. The recruitment campaign which was discreet went underground. However, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police continued to investigate the recruitment activities of the Communist Party of Canada.

By the summer of 1937, there were an estimated 500 volunteers from Canada in Spain. Many of the early volunteers served with the Abraham Lincoln Battalion of the XVth International Brigade. With a growing number of Canadian volunteers, a campaign began among the Canadian members of the International Brigades to form a distinctly Canadian unit. The official date for the establishment of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion was Dominion Day, July 1, 1937 in Tarazona de la Mancha, Spain as a component of the XVth "English-Speaking" International Brigade. The name selected for the Canadian Battalion was in recognition of the leaders of the Rebellions of 1837 in Upper and Lower Canada. The name was popular among Canadians and as early as May 20, 1937 the association "Friends of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion" was formed in Canada. The establishment of a Canadian battalion was intended by the political leadership of the International Brigades to solicit attention and support in Canada for the Spanish Republican cause. Throughout the Civil War, Canadians also served in other units such as the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, the British Battalion, the Palafox Battalion and in artillery, transport, medical and administrative units. In late 1936, Dr. Norman Bethune, a noted surgeon from Montreal, formed and led a Canadian mobile blood-transfusion unit. In June, 1937 he returned to Canada on a speaking tour in support of the Spanish Republican cause.

The "Mac-Paps" as a military unit received approximately two months of formal military training in Tarazona de la Mancha and were sent to the front in September, 1937. At full strength, the Battalion held approximately 600 men and was organized into three rifle companies and one machine-gun company. The machine-gun company was composed predominantly of Finnish-Canadians. They fought their first battle at Fuentes de Ebro on 13 October, 1937 where the Battalion suffered an estimated 60 dead and 200 wounded. The Battalion participated in the defence of Teruel in December-January, the "Retreats" in March-April 1938 and a counter-attack across the Ebro River. The battles and campaigns resulted in numerous casualties in killed, wounded and missing among the Canadians. During these battles, individual Canadians were also captured and taken as prisoners-of-war especially during "The Retreats" of March and April 1938. Others, who were unprepared and unable to withstand the rigours of modern war, broke and often deserted. In 1937, 19 volunteers returned to Canada and 145 returned in 1938 due to wounds or "of their own accord." Other volunteers, however, were politically radicalized by their experiences and several joined the Communist Party of Spain during 1938.

For most of its existence, the Battalion was led by Major Edward Cecil-Smith, a Toronto labour journalist and member of the Communist Party of Canada. In addition to the regular staff of section and company commanders, the Battalion had political commissars at all levels in the Soviet tradition. Among the volunteers from Canada, there were a significant number from the Scandinavian and Slavic left-wing political organizations. Plans were made to establish a French-Canadian company, but there were not sufficient French-speaking volunteers from Quebec. The average age of the Canadian volunteers in 1939 was 33 years old and approximately 75% were born outside of Canada. The majority were unskilled, semi-skilled and manual workers. The largest numbers came from Ontario, British Columbia, Quebec and the prairie provinces. Although nominally a Canadian unit, the Battalion reflected the international composition of the volunteers and included a significant percentage of Americans and Europeans. As the Civil War continued, Spanish recruits replaced casualties and a fourth rifle company was added composed of young Spaniards. After February, 1938, few Canadian volunteers travelled to Spain. By the summer of 1938, the Canadians formed only a minority of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. Of the surviving volunteers, approximately 70% were members of the Communist Party of Canada.

The Republican Government decided to withdraw the International Brigades in September 1938 in the vain hope that the Italian and German military units would also be withdrawn from the Franco side. The Battalion was withdrawn from the front lines on September 23, 1938. A large parade of the International Brigades was held on October 29 in Barcelona where the volunteers were cheered by the Spanish people. In total, there were over 1500 volunteers from Canada serving in Spain at various times during the period 1936-39. Of this number, 238 were killed in action and 118 missing in action. It was the rare volunteer who did not suffer from wounds, sickness or accidents.

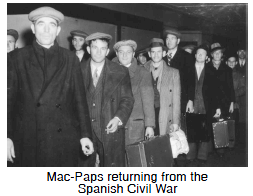

The volunteers were held in Ripoll and in various other locations in Spain prior to their return to Canada. They were interviewed by Canadian immigration officials to determine whether they were in fact Canadian-born, British subjects or Canadian residents. A small number were refused entry into Canada because they were unable to persuade the immigration officials of their Canadian connections. Other volunteers travelled to the United States or to their European countries of origin prior to returning to Canada. The Canadian federal government was reluctant to support financially the return of the Canadian volunteers. After some delay, travel arrangements were concluded and the veterans returned to Canada in February 1939. They were greeted by large crowds at the train stations in Montreal and Toronto and left for their homes across Canada. By April, 646 volunteers had returned to Canada and by May, approximately seventy Canadian volunteers who were held as prisoners-of-war returned. One known Canadian volunteer was held as a prisoner-of-war in Spain until 1942. None of the returned volunteers were prosecuted under the Foreign Enlistment Act.

The Friends of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion had established a rehabilitation service to assist the volunteers with medical and social services. Fundraising campaigns were conducted across Canada in an effort to raise sufficient funds to aid the returned volunteers.

The Spanish Civil War ended in March 1939 with the capture of Madrid and the military victory of the insurgent forces led by General Francisco Franco. In Canada, a Spanish Civil War veterans association was formed in September 1938 to represent the interests and concerns of the veterans, assist Spanish Republican refugees and continue the political campaign against Franco Spain. All the returned veterans became collectively known as the "Mac-Paps" regardless of their service in other units in Spain. There are no records of any Canadians serving with the armed forces led by General Franco.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, a number of Mac-Pap veterans attempted to join the Canadian Armed Forces, but claimed that they were rejected due to their service in Spain. Four veterans were interned by the Canadian federal government in 1940 as part of the attempt to control the activities of the Communist Party of Canada. Other Mac-Paps joined the Canadian Armed Forces after the Nazi German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Approximately 70 served in various allied armed forces and two Mac-Paps were killed in action during the Second World War.

The events surrounding the Second World War soon overshadowed the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War. In the years after 1945, the political climate of the Cold War cast suspicion on the Mac-Pap veterans and their activities because many maintained their membership in the Communist Party of Canada. During these years, several veterans returned to their countries of origin in Europe.

The Mac-Pap veterans association was reorganized in December 1947. A few of the veterans, including Ted Allen, Hugh Garner and William Beeching, wrote articles, short stories and books about the Canadian volunteers in Spain. For most of the veterans, their involvement in the Spanish Civil War remained the defining experience of their lives.

Despite repeated attempts, the veterans were unable to obtain any form of official recognition from the Canadian federal government for their military service in Spain. Almost sixty years after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the campaign by the Mac-Pap veterans resulted in some success when on June 4, 1995, the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board erected a plaque at Queen's Park in Toronto in memory of the "Mac-Paps."

Further Readings and Sources

Allen, Ted and Sydney Gordon, The scalpel, the sword: the story of Dr. Norman Bethune. Boston: Little, Brown 1952.

Allen, Ted, This time a better earth. New York: Morrow 1939.

Beeching, William C. Canadian Volunteers, Spain, 1936-39. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center 1989.

Garner, Hugh, "The Stretcher Bearers" in Hugh Garner, Best Stories. Markham, Ontario: Paperjacks 1983.

Hoar, Victor, and Mac Reynolds, The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion. Copp Clark Publishing Company, 1969.

Momryk, Myron, "Ukrainian Volunteers from Canada in the International Brigades, Spain, 1936-39: A Profile." Journal of Ukrainian Studies, Vol. 16, Nos. 1-2 Summer -Winter, 1991.

Munro, John A., "Canada and the civil war in Spain: repatriation of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion," External Affairs, vol. 23, No.2, February, 1971.

Russell, Hilary, "The Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion," Manuscript on File, Historical Research Branch, National Historic Sites Directorate, Canadian Parks Service, 1984.