One of the ongoing arguments in constitutional history is the struggle between provincial powers and federal powers - who controls what and when can one level of government override the decisions of another?  Confederation was still young when these conflicts were raised by the Manitoba Schools Act, an act which also stirred up another recurring theme of constitution: A constitution is

the system of fundamental

principles according to which a

nation, state or group is

governed.constitutional argument - French/English relations.

Confederation was still young when these conflicts were raised by the Manitoba Schools Act, an act which also stirred up another recurring theme of constitution: A constitution is

the system of fundamental

principles according to which a

nation, state or group is

governed.constitutional argument - French/English relations.

When Manitoba was created it had two public school systems - one French and Catholic, the other English and Protestant, but by 1890 one of the fears of the Métis had come to pass. Immigration from Ontario had created a large English Protestant majority who resented public funding for French Catholic schools.

Responding to this pressure, the province passed the Manitoba Schools Act which created a single, non-denominational school system in English only. Originally the act would have made schooling compulsory schooling: children were required by law to attend school.compulsory, as well, but there was a fear that forcing French Catholics to attend English schools would have caused even more opposition to the bill. (In 1916, Manitoba did make schooling for seven-to-fourteen-year-olds compulsory, joining the general trend in the country.)

The Manitoba Schools Act actually defied both the Manitoba Act and the BNA Act which had provisions to protect denominational: (referring to schools) having to do with some religious group or denomination.denominational schools where they existed at the time a province joined the Dominion.

Catholic leaders in Manitoba and Quebec protested and appealed to the federal government to intervene, but Sir John A. Macdonald did not want to overrule or disallow provincial legislation, especially since education was a provincial matter under the BNA Act. He put it to the courts to decide and after contradictory decisions from different levels of the legal system, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, England ruled in favour of the province.

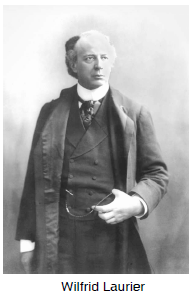

The issue was still being debated during the 1896 election campaign which was won by the first French-Canadian prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier. Promising an amicable solution, Laurier met with the provincial premier Thomas Greenway.

The issue was still being debated during the 1896 election campaign which was won by the first French-Canadian prime minister, Wilfrid Laurier. Promising an amicable solution, Laurier met with the provincial premier Thomas Greenway.

The Laurier-Greenway Compromise which finally ended the controversy, added some measures for language and religious instruction, but took away much of the status of the French language in the province and basically upheld the single school system introduced by Greenway in 1890. The Liberals had established their reputation as a party that would protect provincial rights.