R.L. Gabrielle Nishiguchi is an Ottawa-based researcher/writer. She is currently on contract with the Directorate of History, Department of National Defence. This article was written with information from recently declassified records. Ms. Nishiguchi was historical consultant for "Throwaway Citizens," a documentary about the Japanese deportations produced for CBC-TV's The Fifth Estate.

R.L. Gabrielle Nishiguchi is an Ottawa-based researcher/writer. She is currently on contract with the Directorate of History, Department of National Defence. This article was written with information from recently declassified records. Ms. Nishiguchi was historical consultant for "Throwaway Citizens," a documentary about the Japanese deportations produced for CBC-TV's The Fifth Estate.

Manzo "Jack" Nagano, Canada's first Japanese pioneer, made his trans-Pacific sojourn from Nagasaki, Japan to Victoria, B.C. in March of 1877. Nagano was so determined to begin a new life in Canada, that the young deck hand is said to have hidden from his shipmates in a nearby forest to avoid returning to Japan with them. He was twenty-two. Hardworking, entrepreneurial immigrants like Nagano managed not only to survive, but to thrive. Following in the footsteps of the Chinese, among the first Asians to settle in western North America, he blazed the way for the establishment of a community of his own countrymen. By the outbreak of the Second World War, Japanese Canadians would number slightly over 23,000. Almost without exception, they would be found along Canada's Pacific coast.

Nagano, like so many immigrants of the day, was a jack-of-all-trades, trying his hand at railway construction work, salmon canning, fishing and even selling pick axes and pans to hordes of Klondike-bound prospectors. Yet, during the early years of the new century, he traded in his peripatetic: travelling from place to place.peripatetic lifestyle for that of a city merchant. After hearing a sermon from a Japanese Salvation Army preacher, he became a Christian and eventually opened several stores and restaurants in Victoria. He purchased a hotel to provide temporary shelter for newly-arrived Japanese labourers, some of whom were under contract to work in the great Dunsmuir coal mines of Vancouver Island or on the B.C. section of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Other Japanese settlers eagerly sought jobs as sawmill hands, market farmers, fishermen or, later in the 1920s, as housemaids -- this when "picture brides" began disembarking at the port cities of Vancouver and Victoria. These young, adventurous Japanese women were not unlike the 18th-century filles du roi of Nouvelle France or B.C.'s own British "crinoline contingent" of the 1860s, risking much to marry virtual strangers.

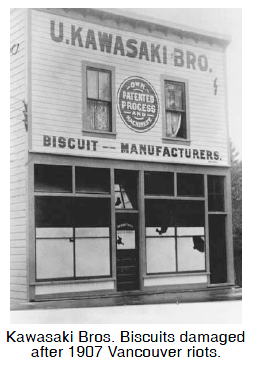

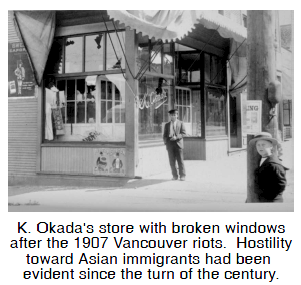

Little by little, the sight of Japanese workers in B.C. became commonplace. In September of 1907, rumours of boatloads of Japanese immigrants sparked rioting on Vancouver streets. Japan agreed to voluntarily limit the number of her citizens emigrating to Canada. For those Japanese who had already settled in B.C. their berry farms in the Fraser Valley, fishing boats along the west coast and small businesses in Vancouver and New Westminster continued to arouse resentment.

Little by little, the sight of Japanese workers in B.C. became commonplace. In September of 1907, rumours of boatloads of Japanese immigrants sparked rioting on Vancouver streets. Japan agreed to voluntarily limit the number of her citizens emigrating to Canada. For those Japanese who had already settled in B.C. their berry farms in the Fraser Valley, fishing boats along the west coast and small businesses in Vancouver and New Westminster continued to arouse resentment.

The first generation Japanese Canadians (Issei) were admired for their industriousness, yet disliked for any successes resulting from it. They owned businesses and homes and were obliged by law to pay income tax but could not vote, having been disenfranchised: deprived of the right to vote.disenfranchised in 1895. Many had Canadian-born (Nisei) children who, for the most part, spoke little or no Japanese.

In December 1941, Canada declared war on Japan after the Japanese attack on the U.S. Pacific naval base at Pearl Harbor. Overnight, 23,149 persons of Japanese ancestry, 75% of whom lived within a 50-75 mile radius of Vancouver, were transformed into potential enemies. Without delay, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (R.C.M.P.) internment: being forced to stay in a certain place.interned thirty-eight Japanese Nationals who were on a special pre-war "suspect" list and sent them to a prisoner-of-war camp in northern Ontario. These men were primarily Japanese newspaper editors, language school teachers and even a tomato farmer with property on one of B.C.'s west coast islands. No criminal charges were ever laid against them. Over half would be released within a year. Next, Canadian authorities impound: seize and put in the custody of a law court.impounded nearly 1200 fishing boats owned by naturalize: grant the rights of citizenship to persons native to other countries; admit (a foreigner) to citizenship.naturalized or Canadian-born Japanese.

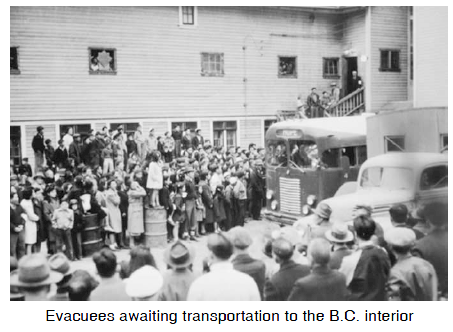

Then, in 1942, Prime Minister Mackenzie King announced that all persons of Japanese ancestry would be moved from the coast, their property confiscate: seize for the public

treasury; seize by authority;

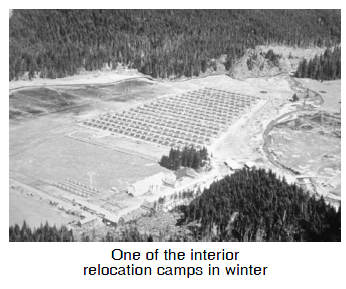

take and keep.confiscated and held in trust by the Canadian government until the end of the emergency. Beginning in March and continuing until the end of October 1942, trainloads of Japanese Canadian men were transported to B.C. and Ontario construction projects, their wives and children to abandoned mining camps and villages in the interior of B.C. Any families wanting to remain together were sent across the Rockies to vast, isolated sugar beet farms in Alberta and Manitoba. Several hundred young Nisei men protested that the government should not treat Canadian citizens this way. They were promptly arrested and thrown into Ontario military prisoner-of-war camps.

Then, in 1942, Prime Minister Mackenzie King announced that all persons of Japanese ancestry would be moved from the coast, their property confiscate: seize for the public

treasury; seize by authority;

take and keep.confiscated and held in trust by the Canadian government until the end of the emergency. Beginning in March and continuing until the end of October 1942, trainloads of Japanese Canadian men were transported to B.C. and Ontario construction projects, their wives and children to abandoned mining camps and villages in the interior of B.C. Any families wanting to remain together were sent across the Rockies to vast, isolated sugar beet farms in Alberta and Manitoba. Several hundred young Nisei men protested that the government should not treat Canadian citizens this way. They were promptly arrested and thrown into Ontario military prisoner-of-war camps.

The B.C. winter of 1942-43 proved to be one of the coldest and harshest on record. The interior settlements consisted primarily of temporary shacks. Insulation was tar paper. There were no mattresses for beds because the Minister of Labour, who was responsible for the well-being of the Japanese Canadians, decided that straw-filled sacks would be better suited to the lifestyle of the evacuees. Canadian-born children, whose main connection to Japan was their surname, woke up in the winter with ice on their pillows and in the summer, covered with bites from fleas which infested their straw bedding. Many of those evacuee: someone who is removed from one place to another place.evacuees who had opted for prairie sugar beet farms faced life in converted chicken coops. During the winter, the mercury often dipped below minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 36 Celsius). Evacuees soon discovered that often their only protection against the cold outside was a layer of dirt they had shovelled around their coops in the fall.

What kept many Japanese Canadians going through this first winter was the comforting thought that when the fighting was over, they would be able to return to their homes and businesses on the coast. On the 19th of January 1943, this hope was skewered. All their property left behind in trust with the federal government would be sold. The evacuees were to live off any money raised in this way. Only after this source of income had been exhausted, would they be provided with any financial assistance. Many were quickly made destitute: lacking such necessities as food, clothing, and shelter.destitute. With no property and no cash reserves, the question arose in everyone's mind: What was to become of Canada's "Japanese Problem?"

By the end of 1944, American President Franklin Roosevelt had decided that all evacuated Japanese Americans would be allowed to return to the U.S. west coast. Canadian civil servants and their political masters were in a bind. They did not wish the evacuees back on B.C.'s west coast and had already sold most of their property to ensure that the Japanese Canadians would not return there. In fact, Japanese Canadians would not be permitted back on the coast until April 1, 1949.

By the end of 1944, American President Franklin Roosevelt had decided that all evacuated Japanese Americans would be allowed to return to the U.S. west coast. Canadian civil servants and their political masters were in a bind. They did not wish the evacuees back on B.C.'s west coast and had already sold most of their property to ensure that the Japanese Canadians would not return there. In fact, Japanese Canadians would not be permitted back on the coast until April 1, 1949.

At first, King's senior bureaucrats had thought to call together a commission to investigate the loyalty of every person of Japanese ancestry in Canada. Those judged disloyal would be deported to Japan after the war. However, setting up a commission to establish the loyalty of over 23,000 persons proved impossible. Thus, the senior bureaucrats returned to their original notion of surveying all Japanese Canadians and asking them whether they desired to go to Japan. Anyone who said yes, would be provided with every means to leave Canada.

From May until the end of summer 1945, every person of Japanese ancestry in Canada (16 years or older) was required by law to sign a piece of paper indicating whether he would go to Japan or move "east of the Rockies." Those relocating to Ontario were offered a settlement subsidy of sixty-five dollars; those opting for Japan, "free passage" plus a "several hundred dollar" grant. The actual sum of two hundred dollars was not decided until December of 1945. Furthermore, it was not made clear to the evacuees that the passage was "free" and the grant was "several hundred dollars" only if the person were completely without resources. Otherwise, the passage cost and grant were to be deducted from any existing funds held by the government in the evacuee's name.

The sick, those who were too elderly to begin life again in the heart of Anglophone Canada, and those who had become destitute living off the sale of their homes, businesses and belongings were perfect candidates for such a programme. Before the official surrender of Japan in September 1945, over 10,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were either "signers" or dependents of "signers." No one had explained to the discouraged evacuees that "signing" was evidence of disloyalty. As well, after Japan's surrender, no application could be cancelled. On the 17th of December, this "transportation" programme legally became a "deport: to banish or expel.deportation" scheme. The deportations were to be carried out by two special executive laws known as Privy Council Orders 7355 and 7356.

Between May 31 and December 24, 1946, 3,964 Japanese Canadians were put onto ships that sailed for war-devastated Japan. Among these persons were invalids on stretchers, psychiatric patients and a First World War shell-shocked veteran. One of the psychiatric patients died within weeks of his landing in Japan. Even for the strong, life was harrowing. Starvation conditions were so severe that war survivors were forced to eat insects for protein. Missionaries reported that there was not even enough flour to make Catholic communion wafers. Many of the sick and the elderly died. The exact number is not known. Desperate deportees wrote poignant letters to the Prime Minister begging to be allowed to come back to Canada. Over the next ten to fifteen years, some did manage to return to Canada, but it was a slow and complicated process.

Bibliography

Books

Adachi, Ken. (1976). The Enemy That Never Was: A History of the Japanese Canadians. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

Kogawa, Joy. Obasan. (1981). Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, Ltd. (Novel: winner of the 1981 Books in Canada First Novel Award & Winner of the Canadian Authors' Association 1982 Book of the Year Award)

Roy, Patricia, Granatstein, J.L., Iino, Masako and Takamura, Hiroko. (1990). Mutual Hostages: Canadians & Japanese During the Second World War. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sunahara, Ann Gomer. (1981). The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians During the Second World War. Toronto: James Lorimer & Co.

Films

"Throwaway Citizens," CBC-TV the fifth estate. Producer/Director: Margaret Slaght, Host: Linden McIntyre, Programme Consultant: R. L. Gabrielle Nishiguchi. Aired: 24 October 1995 (30 minutes). "Throwaway Citizens" received an Honourable Mention at the 1996 BNAI BRITH Media Human Rights Awards as well as first prize at the 1996 Yorkton, Saskatchewan Film Festival.

Redress: footnote to the article

On September 22, 1988, Progressive Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney announced in the House of Commons that a precedent-setting negotiated settlement had been reached with the Japanese Canadian community. An ex gratia payment of $20,000 would be paid to each survivor of Japanese ancestry who could document that he had lived in Canada during the Second World War and had suffered rights violations by reason of race under the federal War Measures Act.