The Mi'kmaq were the major indigenous group occupying

the Maritimes at the time of European contact. They

were part of the Algonquian language group (the two

main language

groups of the

Northeastern

indigenous peoples

were the Algonquian

and the

Iroquoian),

although they had

their own distinctive

dialect.  Close

neighbours of the

Mi'kmaq were the

Malecite (also spelled Maliseet). They

lived mostly in the

western part of

what is now New Brunswick. While the Mi'kmaq were

coastal people, the Malecite depended more on inland

resources and even cultivated corn. We know less about

the Malecite because the early European settlers and

explorers had little contact with them.

Close

neighbours of the

Mi'kmaq were the

Malecite (also spelled Maliseet). They

lived mostly in the

western part of

what is now New Brunswick. While the Mi'kmaq were

coastal people, the Malecite depended more on inland

resources and even cultivated corn. We know less about

the Malecite because the early European settlers and

explorers had little contact with them.

FOOD AND ECONOMY

Hunting and fishing were the main activities of the Mi'kmaq. In winter they would camp in smaller family groups and hunt for deer, elk, seal, beaver, otter, moose, bear and caribou. In the spring and summer they joined with other families to form larger camps. They gathered and boiled maple tree sap in the spring and did a little farming in the summer, but their main food source at this time of year was fish - smelts, herring, sturgeon, salmon, cod and eels.

DWELLINGS

The Mi'kmaq built birchbark-covered wigwams which were light and easy to roll up and carry to a new location. Sometimes wigwams were round with a single fire in the middle. These accommodated 10 to 12 people. Larger wigwams were long with a fire at each end and room for 20 to 24 people.

TRANSPORTATION

The Mi'kmaq had birchbark canoes that could hold five or six people. In the 17th century they added sails to these canoes. In winter they travelled through the snow with the aid of snowshoes, sleds and toboggans. In fact, our word "toboggan" comes from the Mi'kmaq "taba'gan."

SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

The Mi'kmaq had no central governing authority like the Haudenosaunee. There were seven traditional political districts, each headed by its own chief or sagamore. A Grand Chief located in the head district of Cape Breton Island hosted periodic council meetings attended by the band chiefs. The Mi'kmaq were also part of the Wabenaki Confederacy, a loose alliance of several indigenous groups from the northeastern region who met once every few years, sometimes as far away as present-day Boston.

CLOTHING & UTENSILS

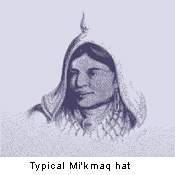

Men wore loincloths in the

summer and fur robes with leggings and moccasins in

winter. Women wore similar robes or long tunics made

from skins which were decorated with paint and porcupine

quills. In the 18th century they began to wear

pointed hats. Most of their domestic tools were made

from lightweight birchbark, often elaborately decorated

with porcupine quills. These quilled boxes and baskets

are quite distinctive to the Mi'kmaq and Malecite.

Men wore loincloths in the

summer and fur robes with leggings and moccasins in

winter. Women wore similar robes or long tunics made

from skins which were decorated with paint and porcupine

quills. In the 18th century they began to wear

pointed hats. Most of their domestic tools were made

from lightweight birchbark, often elaborately decorated

with porcupine quills. These quilled boxes and baskets

are quite distinctive to the Mi'kmaq and Malecite.

RELIGION & FESTIVALS

The Mi'kmaq shared with other Algonquian nations a belief in a supreme being. There were also a number of

lesser gods, some in human form. One of the best

known is Glooscap who was more of a cultural hero than

a god, a human-like being with superhuman abilities.

Shamans shaman: a medicine man in

North American indigenous culture.

Someone with special spiritual

gifts and the ability to heal. could intercede between gods and humans to

cure the sick, predict the future, or help in warfare or the

hunt. The Mi'kmaq held big feasts to celebrate marriages,

funerals, and the beginning of the hunting season.

Elders would give speeches that told family stories and

kept their history alive. The Mi'kmaq chief, Membertou,

converted to Catholicism in 1610 and the Mi'kmaq

remained among the most firmly converted of the indigenous

peoples.

EUROPEAN CONTACT

European contact changed the economy of the Mi'kmaq, bringing them European goods like knives and different foods, most of which were not as healthy for them as their traditional diet. A lot of native people were killed off by European diseases like smallpox. The Mi'kmaq helped the Acadians settle in to their new life. They shared their hunting and fishing techniques with them, told them where to find local resources, showed them how to make clothes and canoes and how to insulate their houses against the winter. The Acadians had fairly good relations with the Mi'kmaq, but they participated, along with the English, when Governor Cornwallis offered a bounty for the dead body of any Mi'kmaq man, woman or child.