The Métis were people of mixed race, the product of a mingling of European fur traders with the Indigenous peoples. Many were French-speaking and Roman Catholic, but some had Scottish and English backgrounds.  By the early 19th century the Métis population had spread from the Upper Great Lakes west to the Red River Valley and south to Arkansas.

By the early 19th century the Métis population had spread from the Upper Great Lakes west to the Red River Valley and south to Arkansas.

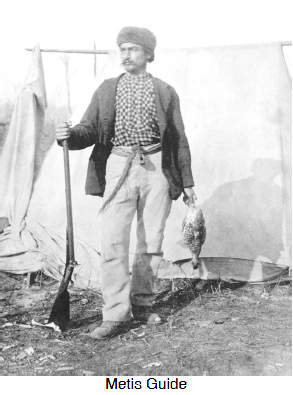

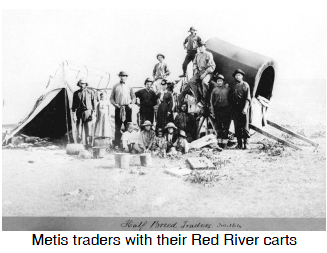

The Métis developed a unique way of life which blended European and Indigenous cultures. Some lived in cabins and did a little farming, but most lived a nomadic life, following the buffalo herds and living in tents. They carried their possessions in vehicles which were an adaptation of French-Canadian wagons called Red River carts. These were made entirely of wood and leather with no iron fastenings so that they were easy to repair, but because they didn't use axle grease, which would have clogged up with prairie dust, the rubbing of wood on wood made a horrible racket which could be heard from great distances.

The wheels were up to two metres in diameter and spaced wide apart to lessen the chance of sinking into the prairie mud. And when the Métis had to cross a river, they simply removed the wheels, tied them underneath, and used the cart like a raft.

The Métis were important to the North West fur trading company because the Indigenous wives were skilled at making pemmican, a staple food for the survival of the fur traders during their long journeys. When the rival Hudson's Bay Company tried to move in settlers to establish farms in the Red River area in the early 1800s, the Nor'Westers encouraged the growing national sentiment of the Métis people and their territorial claims on the area. Of the 12,000 non-Indigenous people living along the Red River at the time of Louis Riel in 1870, 10,000 were Métis.

The Métis were important to the North West fur trading company because the Indigenous wives were skilled at making pemmican, a staple food for the survival of the fur traders during their long journeys. When the rival Hudson's Bay Company tried to move in settlers to establish farms in the Red River area in the early 1800s, the Nor'Westers encouraged the growing national sentiment of the Métis people and their territorial claims on the area. Of the 12,000 non-Indigenous people living along the Red River at the time of Louis Riel in 1870, 10,000 were Métis.