T

he men were young, of course, many just 18 to 24 years old. The roads were narrow dirt tracks switchbacking over steep, volcanic mountains. Temperatures hovered around 37 degrees, turning water bottles into hot water bottles, as one soldier put it. Three dry and dusty weeks into the campaign, there was a five-hour downpour, and all the troops relished the chance to shower off the dirt caked to their skin. By this time they were well into the middle of the island where their enemy was the fierce Hermann Goering division of the German army.

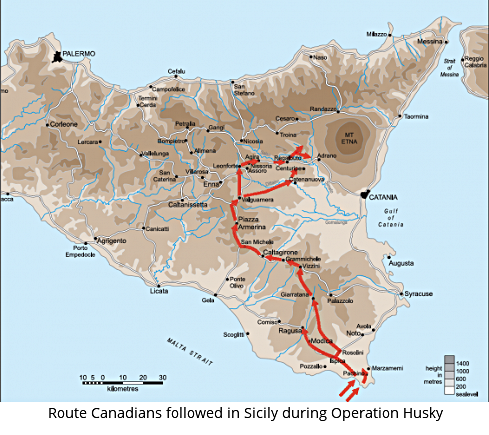

For six weeks, from July 10th to August 17th 1943, the Canadians, fighting as an independent unit for the first time, slogged through the interior of Sicily as part of Operation Husky, the first stage of taking back Europe from the Nazis after four years of war. Meanwhile, the Americans skirted the more level western coastline of the island and the British came up the east side, each competing with the other for glory.

For six weeks, from July 10th to August 17th 1943, the Canadians, fighting as an independent unit for the first time, slogged through the interior of Sicily as part of Operation Husky, the first stage of taking back Europe from the Nazis after four years of war. Meanwhile, the Americans skirted the more level western coastline of the island and the British came up the east side, each competing with the other for glory.

American General Patton wrote in a letter, “This is a horse race in which the prestige of the US Army is at stake...we must take Messina before the British.”

That may be the way the generals saw it. For the soldiers, pushing through, village by village, mountaintop by mountaintop, it was no game.

Sicily, a rural mountainous island known for its orange groves and almond orchards, olives and the Mafia, sits strategically in the Mediterranean off the foot of Italy. The Canadian contingent was 25,000 strong. All men and materials were brought in by sea, making it the largest amphibious operation yet, though D-Day, a year later, would be bigger still.

In the first few days the Canadians passed through an area that is now a Unesco World Heritage site. Today tourists come to this southeast corner of Sicily to see the restored baroque architecture. But the young Canadian lads were eyeing the pillboxes, watching for snipers and lookouts. In the early days many Italian soldiers surrendered without too much resistance and the local people gave them grapes and oranges to quench their thirst in the scorching heat.

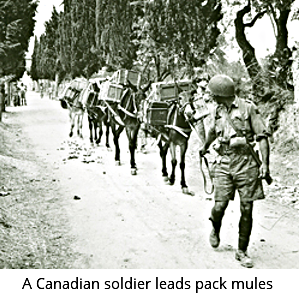

Further inland it was a different story. These mountaintop towns were held by German troops. Canadians persevered through Grammichele, Piazza Armerina, Agira, Regalbuto. Often mules were used for transport, as they were better suited to the winding dirt tracks than big tanks, but they made progress slow. Sometimes when the soldiers reached towns they discovered streets reduced to rubble by aerial bombardment.

Further inland it was a different story. These mountaintop towns were held by German troops. Canadians persevered through Grammichele, Piazza Armerina, Agira, Regalbuto. Often mules were used for transport, as they were better suited to the winding dirt tracks than big tanks, but they made progress slow. Sometimes when the soldiers reached towns they discovered streets reduced to rubble by aerial bombardment.

Other towns seemed unassailable. At Assoro, for instance, Germans looked down from the town which sat on the west side of the mountain, a perfect vantage point for picking off would-be attackers. The east side was a sheer cliff and thought to be an impossible approach. But Canadians of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment, known as the Hasty Ps, scaled it at night and surprised the Germans by attacking from above the next morning.

The Canadians were told to stop at Adrano, at the foot of Mt. Etna, whose towering presence had loomed in the distance throughout their journey. The British and Americans pressed the final miles to cut off the Germans at Messina. Patton won his race, but not before lots of German men and materials had been safely evacuated to the mainland of Italy where they were used against our soldiers in that long and difficult campaign. Many historians comment about the failures of the high command and the negative effect of personality conflicts and national rivalries at the top. But the soldiers did their jobs.

Operation Husky did succeed in gaining back the first European soil for the Allies. In the midst of it, Mussolini resigned and soon after Italy surrendered, another goal of the campaign. It started a second front forcing Hitler to back off his aggressive attack on our ally, Russia. And it provided a rehearsal for the larger amphibious landing on the beaches of Normandy, France in June of 1944. As well, it was the first time Canadians had fought as an independent unit. Their young commander was Guy Simonds. 1200 Canadians were wounded in Sicily and 562 died there. 490 of them are buried in the Canadian cemetery at Agira.

For their efforts, the soldiers fighting in Sicily and Italy became known as the “D-Day Dodgers”, a careless epithet supposedly delivered by Lady Astor, but embraced by the soldiers themselves who, with some sarcastic humour, turned it into the song, “We are the D-Day Dodgers, in sunny Italy...”

Next: D-Day Landings

in Normandy >>