Dr. Carl A. Christie is a historian who specializes in Canadian military history. He has written a book on Ferry Command titled, Ocean Bridge: The History of RAF Ferry Command, published by University of Toronto Press.

Dr. Carl A. Christie is a historian who specializes in Canadian military history. He has written a book on Ferry Command titled, Ocean Bridge: The History of RAF Ferry Command, published by University of Toronto Press.

Canadians were intimately involved in all aspects of the struggle that helped the Allies defeat the Axis Powers during the Second World War and laid the foundations for many of the things we now take for granted. One such contribution, that we seldom hear much about, was that made by the thousands of people, in and out of uniform, who toiled for Royal Air Force Ferry Command from headquarters in Montreal. These unsung heroes not only helped win the war by delivering almost 10,000 military aircraft, as personnel and materiel, to battlefronts around the world, they also left a lasting legacy of intercontinental air travel that has become a key part of our lives today.

The story of Ferry Command has its origins well before the war. In June 1919, only seven months following the armistice: a temporary stop in fighting by agreement on both sides; truce.armistice that ended the Great War, two British airmen, John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown, had shown that the treacherous skies of the North Atlantic could be conquered by flying nonstop from Newfoundland to Ireland. Eight years later Charles Lindbergh, the American "Lone Eagle," captured the hearts of millions of people on both sides of the Atlantic when he made it across alone from New York to Paris. Seldom has a human being been so lionized; he was celebrated as a hero by Europeans and North Americans alike. After his feat underlined the possibility, even the feasibility, of linking the New World and the Old by air, others tried to emulate him many dying in the attempt.

Powerful organizations and even governments joined in the race to make flying across the Atlantic a regular occurrence, even though no one had yet built an aeroplane with the necessary combination of range and payload to make it financially viable. The first experimental commercial flights were made by flying boats of Britain's Imperial Airways and Pan American Airways of the United States. At the time, this type of aircraft was linking many parts of the world over what might be termed medium-range air routes of a few hundred miles. The flying boat offered a number of advantages; in particular, it needed no runway on which to take off and land. Still, its development had reached a plateau and most aviation experts recognized that the next generation of airliners would have to be land planes. And, on the North Atlantic, all the flying that did take place was done in the summer. Only the foolhardy would have attempted to make that dangerous crossing in the more hazardous ice and snowstorms of the fall or winter.

During the 1930s, many individuals involved in the new world of aviation (with aircraft manufacturing companies and airlines, as well as a few politicians and civil servants) could see a new era dawning in which the continents would be linked by regularly scheduled airline service. The United States, the United Kingdom, the Irish Free State, the Dominion of Canada, and Newfoundland (at that time still a separate member of the British Empire) worked together towards the development of a commercial air service across the Atlantic Ocean.

Canada and Britain helped Newfoundland build a giant airport in the wilderness near Gander Lake, a little more than 200 miles west of St. John's, in anticipation of a new generation of land-based aeroplanes that could commence the awaited service. However, by the time war broke out in September 1939 the Newfoundland Airport, as it was officially named, had no regular user. The flights of Imperial Airways and Pan American Airways were not much more than experimental and, even then, were restricted to flying boats and only in the warmer months of the year. No official at the British Air Ministry appears to have considered using the airport as a staging base for the delivery of new military aircraft built in North America; the distance was too great and the skies of the North Atlantic were simply too treacherous.

In the summer of 1940, following the fall of the Low Countries, Denmark, Norway, and France to the German blitzkreig, the war suddenly took a nasty turn for Great Britain, whose citizens found themselves standing almost alone against the aggressive expansion of Nazi tyranny under Adolf Hitler. Suddenly faced with a life-and-death struggle for its way of life, the Air Ministry agreed to assume responsibility for the outstanding aircraft orders the French had placed with American manufacturing companies. Unfortunately, this came just as German U-boats were sending greater and greater numbers of freighters, and their precious cargoes of war supplies, to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.

Of course, even before German submarines complicated the issue, surface delivery of aircraft was a slow and expensive business. Each plane had to be at least partially disassembled, loaded into the cargo-hold or lashed to the deck of a freighter (which usually could not sail until other ships had gathered to form a protective convoy), and then, on reaching Britain, had to be reassembled and test-flown before it could be ferried to its RAF unit. Operational squadrons, losing aircraft at an alarming rate, were desperate for new machines and could not wait the several months needed to deliver new aeroplanes in this manner. Even so, the air marshals of the RAF felt it was the only way it could be done. They never dreamed of simply flying the planes over.

Nobody knows who first made the suggestion. However, when Lord Beaverbrook, the Canadian-born press magnate serving as Prime Minister Winston Churchill's Minister of Aircraft Production, learned about the idea of flying new aircraft under their own power from the factories in the United States to RAF operational squadrons in Britain, he seized upon it. Officials at the Air Ministry and the RAF said it could not be done. The skies of the North Atlantic were too dangerous and the numbers of aircraft involved would require that inexperienced aircrew make the trip. To this point only the most seasoned and accomplished flyers had made the attempt and, even then, only with the full backing of aviation companies and only in the summer.

George Woods Humphery, recently retired general manager of Imperial Airways, assured Beaverbrook that he could do the job, provided he could have some of his "old Atlantic team" and as long as some existing organization looked after the administrative details. This little matter was settled with a telephone call from one of the minister's assistants to Sir Edward Beatty, president of the Canadian Pacific Railway and, apparently, an old friend of both Beaverbrook and Woods Humphery. (Beatty already had considerable responsibility for co-ordinating the movement of North American war materials to Britain; he literally worked himself to death on the wartime job.) Within days of the proposal's first appearance on the records of the Ministry of Aircraft Production, a handful of experienced aircrew from British Overseas Airways Corporation (or BOAC, which had replaced Imperial Airways as Britain's flag carrier on international air routes in September 1939) sailed for North America to prepare to ferry new aeroplanes across the Atlantic Ocean to the RAF.

While the Newfoundland Airport provided the obvious jumping off point for the long flight over the ocean, it was too isolated to serve as the headquarters of the new organization. Montreal, conveniently situated at the western end of the great circle route following the natural curvature of the earth over the North Atlantic, and thus closer to Europe than the cities of the U.S. eastern seaboard, became the natural choice. And, of course, no centre in the still-neutral United States could be chosen for such a role.

By August, D.C.T. "Don" Bennett, A.S. Wilcockson, R.H. Page, and I.G. "Ian" Ross, were setting up their offices in the CPR's Windsor Street Railway Station in Montreal. All carried both pilot and navigator qualifications and had flown Imperial Airways' flying boats. Ross, a Canadian, had flown at home as a bush-pilot before joining the British airline. Wilcockson, as the former head of Imperial's Atlantic Division, brought highly useful managerial experience. Bennett, probably the single most important individual in getting the Atlantic ferrying scheme launched successfully, later gained fame as the leader of Bomber Command's famous No. 8 "Pathfinder" Group. Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris called him "the most efficient airman" he had ever met.

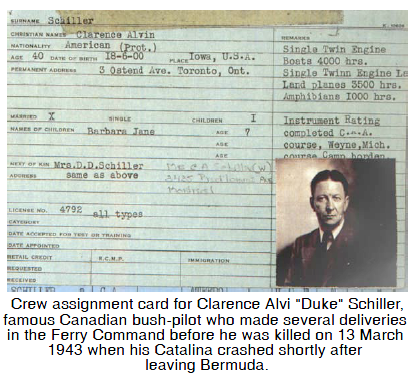

Given the wartime situation, secrecy was essential. Nonetheless, experienced pilots and radio operators were urgently required if the scheme was to have any chance of success. The organizers dared not advertise, but they did put the word out on the aviation grapevine that aircrew were needed in Montreal for an important job related to the war. Neither the RAF nor the Royal Canadian Air Force could spare any aircrew at this stage of their development so civilian volunteers would have to be recruited for the assignment. Most of the pilots in the early months came from the non-belligerent United States.

American airmen learned about the Atlantic ferry scheme from a clandestine organization established by Clayton Knight, an American aviation artist and First World War flyer. With his friend Homer Smith, a Canadian-born businessman, he established a committee, with offices in major U.S. cities, that cultivated contacts in the aviation community, identified instrument-rated pilots with more than 300 flying hours on their logbooks, and helped those who wished to volunteer find their way to RCAF recruiting units in Canada. This violated U.S. neutrality laws, but the White House, under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, chose to look the other way as long as the Clayton Knight Committee kept its activities low-key. By the end of November 1940 it had sent 380 American pilots to Canada. Sixty-two met the stringent qualifications required to ferry a plane across the Atlantic; most of the remainder did important work flying with the schools of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), which turned out more than 130,000 qualified aircrew for the air war.

Volunteers who survived the careful initial scrutiny and testing of Bennett and Wilcockson trained at St. Hubert airport southeast of Montreal to familiarize themselves with the Lockheed Hudson, chosen as the aircraft to make the first, experimental delivery flights. The twin-engine bomber did not have the natural range to fly from Newfoundland to Britain. However, it was thought possible with the addition of overload fuel tanks in the fuselage. This, of course, made an already dangerous undertaking even more so; one of the original members of the ferry organization called these first aeroplanes delivered under their own power across the Atlantic "flying gas tanks." It took little imagination to realize what a crash would mean for the crew. Even so, the Ministry of Aircraft Production apparently decided that desperate times required desperate measures: if at least 50 per cent made it across the Atlantic the experiment would be judged a success and the organization would carry on. A willingness to accept such a high loss-rate must surely speak volumes about the precarious situation in which the United Kingdom found itself.

By October the first Hudsons had arrived at St. Hubert and, with the assistance of RCAF and Trans-Canada Airlines groundcrew, preparations proceeded at a frantic pace to check them out, to prepare them and their crews, and to fly them to the British Isles via Newfoundland. Getting the planes to Montreal required an imaginative circumvention of the U.S. neutrality laws. American law prohibited citizens of a belligerent power from flying planes in the United States and decreed that aircraft could not be flown out of the country for the use of a nation at war. To get around this, American civilians employed by Lockheed Corporation flew them from the factory in California to Pembina, North Dakota. There, horses pulled them a few yards across the 49th parallel to Emerson, Manitoba, before crews of the CPR Air Services Department finished the journey to Montreal along the Trans-Canada Airway (built as a make-work project during the Great Depression). It is interesting to note that, while the practice of towing aircraft across the border ceased in the spring of 1941, it did happen with a considerable number of aircraft at more than one location, from Sweetgrass, Montana to the maritime provinces.

Between 29 October and 9 November, seven newly assembled ferry crews flew Lockheed Hudson Mark IIIs from St. Hubert to Gander, as the Newfoundland Airport was rechristened during the war. Each of the civilian crews found their own way as Don Bennett, overseeing the operation, tried to prepare them for the type of conditions they would encounter on the hop over the ocean. They would not, however, fly all the way to Britain alone. It had been decided, because of a shortage of qualified navigators, that deliveries would be made in a loose formation of seven aircraft with the lead plane flown by an experienced BOAC pilot-navigator.

The Australian-born Bennett led the initial group himself. His co-pilot came from the United States, his two radio operators from Britain and Canada. The other six Hudsons each carried a crew of three, a pilot, a copilot, and a radio operator. All the pilots and co-pilots were either British or American; six of the radio operators were Canadian. The last were a particularly interesting group; they had all been working as radio operators with the Canadian Department of Transport and had answered a call for volunteers for an important war job in aviation. Few had ever flown before they arrived in Montreal; none had made a long-distance flight. In the end, many spent the entire war ferrying aircraft to operational theatres around the world. Like their crewmates at the start of the ferry scheme, all were civilians. At least 75 lost their lives doing this job.

It is also worth noting that the entire aircrew pool for transoceanic ferrying throughout the war was male. Women pilots were not welcome. About a dozen made transatlantic delivery flights as supernumerary co-pilots, but none captained an aircraft on such a trip. It was expressly forbidden by all the organizations involved. Women, including a number of Canadians, did do yeoman work ferrying aeroplanes from factories and repair units to operational squadrons with Britain's Air Transport Auxiliary in the United Kingdom and with the Women's Airforce Service Pilots within the continental United States.

On the evening of 10 November 1940, after ice from an early winter storm was chipped off, seven Hudsons took off and headed east across the forbidding skies of the Atlantic Ocean. Twenty-two men were trying to help win the war; they were also about to make history. Nobody had flown the North Atlantic this late in the year. And they were trying to do it in formation, at night minus the usual navigation lights (to avoid being spotted by marauding German aircraft), and with no navigator in most of the planes. Meteorology lacked the precision it later acquired and, as a consequence, the weather forecast was considered reliable for no more than about the first half of the flight plan. Still, the briefing provided to the crews was remarkably detailed for the day. It was given, as others would be hundreds of more times before the war was over, by Patrick McTaggart-Cowan, a Canadian Rhodes Scholar who already had North Atlantic forecasting experience. The Department of Transport loaned him to the ferry organization for the duration of hostilities where he served as its chief meteorologist in North America. Many veterans of the operation remember him as "McFog" and consider him one of the ferry service's key figures.

As many had feared, deteriorating weather conditions prevented the first flight from making it all the way across in formation. Bennett, a nitpicky perfectionist, had prepared for this eventuality by giving each pilot detailed instructions on how to find his way across if they had to break formation. Some crews had some scary moments, but all made it safely to Aldergrove, near Belfast in Northern Ireland, chosen as the destination because of concern about the Hudson's range. Flying times ranged from eleven hours to almost thirteen for the last Hudson to touch down. The next day they flew to an RAF station near Liverpool. Officials immediately hustled the airmen onto a ship bound for North America. With no celebration and no opportunity to experience Britain at war, they were disappointed. They had made history by flying the Atlantic and now they were quietly hurried aboard a ship which, as part of a slow convoy, would take many days to get them back to Canada.

Bennett travelled to London to report the success of the experiment to Beaverbrook. He found the Minister "smiles from ear to ear. And how the Beaver can smile!" In some ways the venture had been too successful. Bennett wanted to have enough navigators so that each aircraft could carry one and find its own way across. It took a couple of (non-fatal) accidents and the safe arrival of only four aircraft from the fourth formation flight, at the end of December, to convince Beaverbrook that Bennett was right. In January 1941, it was decided therefore to augment the mixed-nationality civilian crews with freshly graduated air navigators from the schools of the BCATP in Canada and to dispatch the planes individually across the Atlantic.

By the new year the experiment of ferrying new planes from North America to the British Isles was clearly an immense success. Twenty-five desperately needed aircraft had reached Britain only weeks, and in at least one case only a few days, after rolling off the assembly line in California, a huge improvement over surface delivery. And by the middle of December, with the extended range of the Hudson confirmed, Prestwick, Scotland had become the destination and the eastern terminus of the ferry operation.

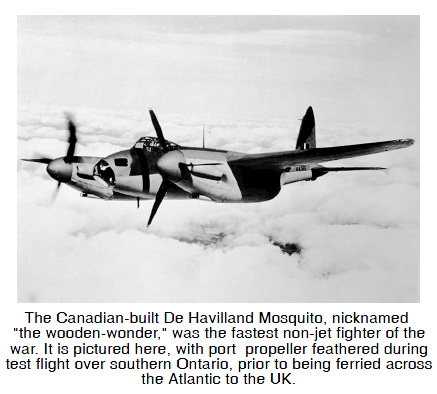

Other aircraft types - notably Consolidated PBY Catalinas and B-24 Liberators, Lockheed Venturas and Lodestars, Douglas DB-7 Bostons, Martin B-26 Marauders and A-30 Baltimores, North American B-25 Mitchells, Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, and Douglas DC-3 Dakotas - soon joined the Hudsons sitting on tarmacs awaiting favourable weather forecasts for the overseas crossing. Eventually, more than a thousand Canadian-built planes were delivered as well - De Havilland Mosquitoes and Avro Lancasters.

Work was begun, as soon as the first flights proved the practicability of the scheme, to build a more permanent organization and to incorporate freshly graduated air navigators into the arrangements. Experienced veterans of Atlantic flying gave the young navigators a special course on transatlantic flying before matching them up with civilian pilots and radio operators.

With shortages of all specialties always a problem, when the new system worked it was quickly expanded to include other aircrew trades. Soon the old hands were talking about "kids flying the Atlantic." These top graduates of the training plan became known as "onetrippers," making one or two overseas delivery flights before being posted to an operational unit. Experienced air force officers needing to get to the other side of the ocean also volunteered to work their way over as onetrippers with a ferry crew. Meanwhile, as the pool of available flying personnel was expanded in these ways, a number of Canadian business executives joined the organization as "dollar-a-year men." As the term implies, these were volunteers who worked for almost nothing to assist the war effort.

The most notable Canadian executive recruited to help with Beaverbrook's grand scheme to ferry aircraft overseas was C.H. "Punch" Dickins, who transferred from Canadian Airways to take over the growing Atlantic Ferry Organization, or "ATFERO" as people were calling it. He had flown with the British Royal Flying Corps during the First World War, where he won a Distinguished Flying Cross, and as a bush pilot in the intervening years. The latter career had earned him some fame, as well as an OBE, for his pioneering work in commercial aviation in western and northern Canada, and a promotion to the executive offices of Canadian Airways. He is credited with overseeing ATFERO's tremendous growth and smoothing its transition to the next phase of its organizational history, while helping to keep U.S.-built planes flowing to the RAF as an important member of the British Air Commission in Washington.

As those in the know learned about ATFERO, some tried to hitch rides to new assignments overseas. One of the first such passengers was Major Sir Frederick Banting, who had won the Nobel Prize as a co-discoverer of insulin and was now co-ordinating medical research to assist the military. During the evening of 20 February 1941 he left Gander in a Hudson piloted by Joe Mackey, an American civilian who had already captained an aircraft as part of the second formation flight at the end of November. Unfortunately, this particular plane developed engine trouble and crash-landed on a lake only a few minutes flying time from Gander. The pilot survived but Banting, along with Pilot Officer William Bird, RAF, and the Canadian radio officer, William Snailham, were killed. These were the first fatalities suffered on a delivery flight, but they would not be the last. By the end of the war over 500 men had died ferrying North American-built aircraft to operational squadrons overseas, more than 200 of them Canadians.

Shortly after the Banting tragedy, the RAF assumed responsibility for the delivery operation it had originally opposed. The civilian organization was retained, but with a veneer of military officers under Air Chief Officer Sir Frederick Bowhill, and a new name: RAF Ferry Command.

May 1941 brought another big change. With the production of aircraft and the need for them fast outstripping the availability of aircrew, BOAC agreed to operate a Return Ferry Service to fly the men back to Montreal. Many more planes could then be ferried without increasing the number of flyers involved by speedily returning airmen to the western terminus to pick up new delivery aircraft. Aircrew found the trip back worse than the delivery flight. BOAC used four-engine Liberator bombers hastily modified to carry people rather than bombs. Unfortunately for the passengers, this conversion simply involved boarding over the bomb-bay, putting in some oxygen tanks with rubber tubes on which to suck, and throwing in some mattresses. In this manner, reclining in the spartan bomb-bay of a bomber and bundled up in the warmest flying gear and sleeping bags, eighteen to twenty passengers endured the fifteen-hour flight, against the prevailing winds, from Scotland to Montreal. The fact that the Return Ferry Service lost 43 aircrew in two horrendous crashes in Scotland within five days in August 1941 did little to instill confidence in the service.

By the summer of 1941 Ferry Command had outgrown St. Hubert. In September it moved to a new airport just west of Montreal at Dorval, which quickly became one of the busiest in the country. By 1943, with the delivery aircraft increasingly called upon to carry important passengers and cargo when they could manage it, the organization became RAF Transport Command. The ferry responsibility fell to No. 45 Group, still with headquarters at Dorval. Its staff, however, continued to refer to their organization as Ferry Command, as its veterans still do.

Even before the militarization of the operation by the RAF as Ferry Command, ATFERO had co-operated with the Americans, and vice versa. Months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, U.S. Navy flyers made flights from Bermuda to Scotland as part of the crews of twin-engine Catalina flying boats being ferried to Britain. Other Catalinas and Mitchells were delivered across the Pacific Ocean to Southeast Asia over U.S.-maintained air routes. At the same time, the U.S. government and Pan American Airways developed an airway across the Caribbean, around the coast of South America, and across the Atlantic Ocean via Ascension Island to West Africa. From there planes flew to North Africa, the Soviet Union, and India via the subsaharan transafrica airway that Pan Am helped Britain to improve and maintain. Cairo became an important centre for hundreds of airmen from Canada and other countries ferrying aircraft to Commonwealth and Allied air forces in far-off exotic theatres of war.

The United States took a keen interest in Ferry Command activities. American influence forced Canada to construct an alternative airfield to Gander as a jumping off point for transatlantic flights. Canadian workers and Canadian money built Goose Bay in Labrador in only a few months, a huge achievement, but airmen from the United States and Britain as well as Canada manned and ferried planes through this important facility. At the same time Canadians and Americans built landing strips, weather and radio stations throughout the Canadian arctic. Originally the Americans had wanted to use these bases, no more than 400 to 500 miles apart, to fly shorter range single-engine fighters to Britain. These plans never reached fruition. However, the basic infrastructure survived the war and left Canada with a network of extremely useful communications and transportation facilities in the north.

After the war, commercial airlines used the airfields and other facilities developed for the air force throughout Canada, and indeed the world. The expansion of civilian aviation in the decade or two following the Second World War could not have happened without the infrastructure left over from the conflict. Equally essential were the thousands of trained personnel looking for employment in peacetime aviation. Less visible, but no less important, were the procedures developed during the war to gather information about the weather, to prepare forecasts, to communicate it to the crews of aircraft, indeed to communicate with airmen at any point in their flights, and to control the flying routes themselves to prevent tragic collisions in increasingly crowded skies. Officers of Ferry Command, many of them Canadian, led in all these areas and bequeathed a lasting legacy to the postwar world.

Even before the end of hostilities, nations, companies, and individuals tried to position themselves to gain an advantage when peace arrived. Major decisions were taken at international civil aviation conferences in 1944 and 1945. There the Allied Powers adopted a system of air traffic control for the world that was based on the one that had been developed by Canada and the United States and agreed to by Britain, largely to handle transatlantic flying. Ferry Command had been instrumental in this process. Delegates to these conferences decided to make Montreal the headquarters of the new Provisional International Civil Aviation Organization or PICAO, at least partly because of the important role the city had played in the world-wide activities of Ferry Command. ICAO, which soon dropped the "Provisional," still has its headquarters in Montreal. The thousands of people who worked in Montreal and around the world to deliver almost 10,000 bombers, transports, and reconnaissance aircraft to operational squadrons of the Commonwealth air forces not only helped win the war against Nazi tyranny, they also helped lay the foundation for today's international system of aviation.

Further Reading

Carl A. Christie, Ocean Bridge: The History of RAF Ferry Command (Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press; Leicester, Eng.: Midland Publishing, 1995)