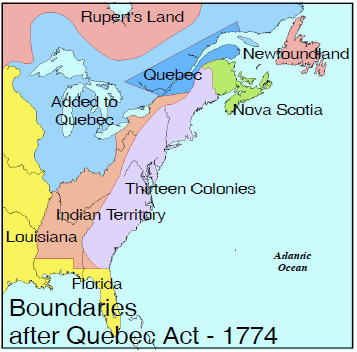

Following the Conquest, North America consisted of three British parts: Acadia, Quebec and the Thirteen Colonies. The challenge facing Great Britain's George III was to persuade his new French Catholic subjects to follow an English Protestant king.  He was particularly anxious to have a stable colony in Quebec because of increasing rumblings of discontent and the threat of revolt in the Thirteen Colonies to the south.

He was particularly anxious to have a stable colony in Quebec because of increasing rumblings of discontent and the threat of revolt in the Thirteen Colonies to the south.

George and his advisers, including the Governor, Guy Carleton, decided that the key to habitant habitant: a farmer in New France. loyalty was gaining the support of the influential members of Quebec society, namely the wealthy seigneurs seigneur: a landowner in New France whose estates were originally granted by the King of France. He also administered justice within his seigneury. and the priests. The result was a document called the Quebec Act which was actually quite progressive for its time. To keep the church happy, Roman Catholics were given political and religious freedoms that they wouldn't have in Great Britain for another 50 years. French language rights were recognized and French civil law civil law: law that deals with private rights (property and the individual), as opposed to "criminal" law which involves crimes against the community. French civil law is written down, or statute law, as opposed to common law. continued to apply in local disputes so that the seigneurs could retain their traditional judicial powers. British law would be used only in criminal cases.

Unconsciously, perhaps, the Quebec Act embodied a new principle in colonial government - the freedom of non-English people to be themselves within the British Empire. It also began what was to become a tradition in Canadian constitutional history - the recognition of certain distinct rights, or protections for Quebec - in language, religion and civil law.

Unconsciously, perhaps, the Quebec Act embodied a new principle in colonial government - the freedom of non-English people to be themselves within the British Empire. It also began what was to become a tradition in Canadian constitutional history - the recognition of certain distinct rights, or protections for Quebec - in language, religion and civil law.